The Bitcoin halving, which is also known as “the halvening,” is the name for one of the most hotly anticipated events in Bitcoin’s history.

In May 2020, the number of bitcoin (BTC) entering circulation every 10 minutes – known as block rewards – dropped by half, from 12.5 to 6.25. It’s a milestone that was easy to see coming because it happens every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years) and had happened twice before 2020.

The allure of possible riches is what draws so much attention to these events. The number of new bitcoin entering circulation shrinks, but demand should, in theory, stay the same, possibly driving up the bitcoin’s price. And so the event has inspired passionate debate about bitcoin price predictions and how the market will respond.

“The theory is that there will be less bitcoin available to buy if miners have less to sell,” said Michael Dubrovsky, a co-founder of PoWx, a crypto research nonprofit.

But the periodic decline in Bitcoin’s minting rate could have a deeper significance than any near-term price movements for the functioning of the currency. The block reward is an important component of Bitcoin, one that ensures the security of this leaderless system. As the rewards dwindle to zero in the decades ahead, it could potentially destabilize the economic incentives underlying bitcoin’s security.

For those trying to make sense of this complex topic, here’s everything you need to know.

What is the bitcoin halving?

New bitcoins enter circulation as block rewards, produced by the efforts of “miners” who use expensive electronic equipment to earn, or “mine,” them.

Roughly every four years, the total number of bitcoin that miners can potentially win is halved.

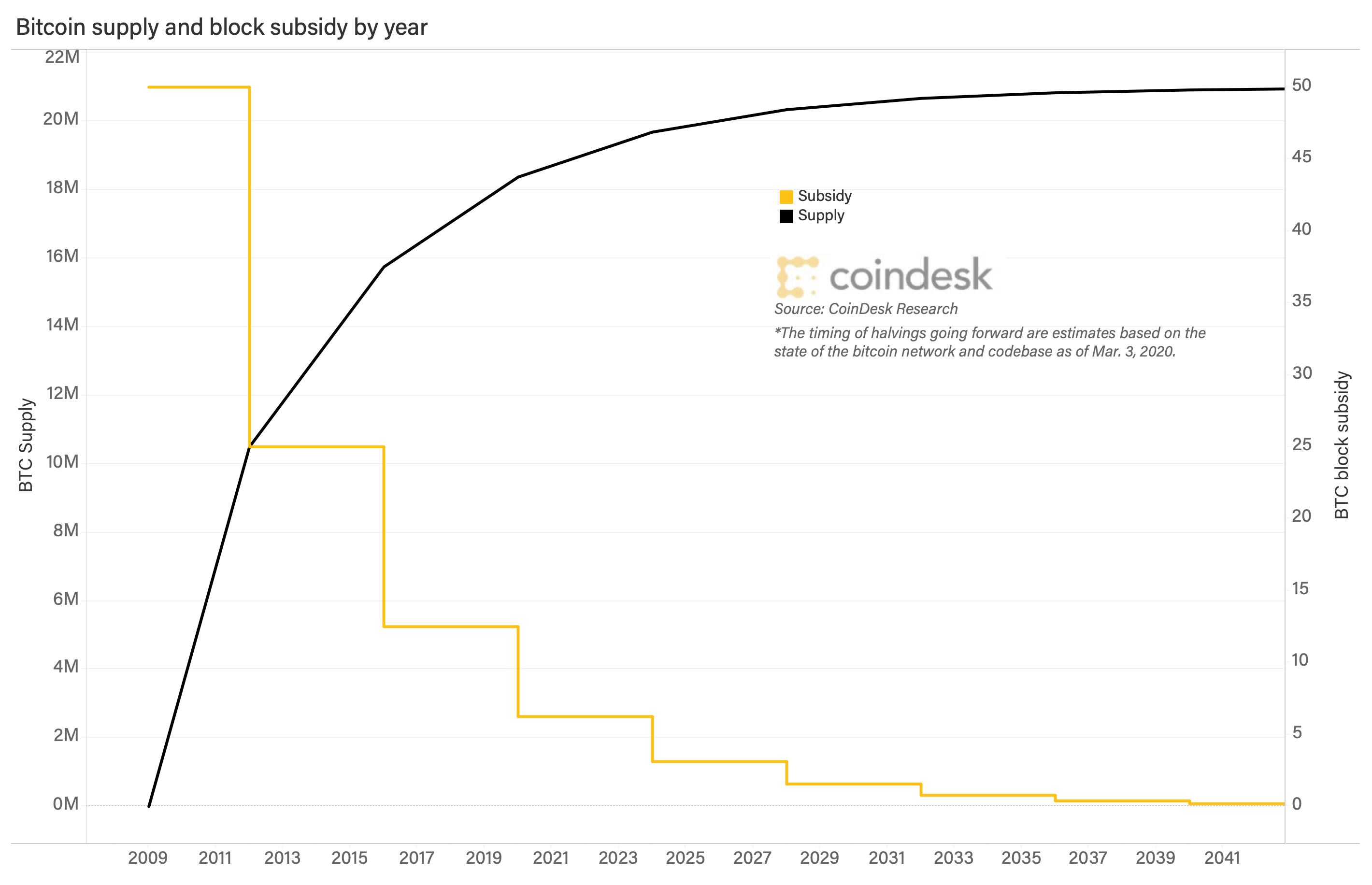

In 2009, the system rewarded successful miners with 50 bitcoin every 10 minutes. Three halvings later, 6.25 bitcoins are being dispensed every 10 minutes.

The process will end once the number of bitcoin in circulation reaches 21 million. A popular estimate is that it will occur sometime near the year 2140.

Who chose the Bitcoin distribution schedule? Why?

Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, who may have been an individual or a team, disappeared about a year after he, she or they released the software into the world. So, he or she or they (we’ll just go with “they” from now on) are no longer around to explain why they chose this specific formula for adding new bitcoin into circulation.

But early emails written by Nakamoto shed some light on the mysterious figure’s (figures’) thinking.

Shortly after releasing the Bitcoin white paper, Nakamoto summarized the various ways their chosen monetary policy (the schedule by which miners receive block rewards) could play out, pondering the circumstances under which it could lead to deflation (when a currency’s purchasing power increases) or inflation (when the prices of goods and services purchasable with a currency increase).

At the time, Nakamoto couldn’t have known how many people would use the new digital money (if anyone).

They elaborated very little on why they chose the particular formula they did: “Coins have to get initially distributed somehow, and a constant rate seems like the best formula,” the wrote.

With most state-issued currencies a central bank, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, has tools at its disposal that enable it to add or remove dollars from circulation. If the economy is floundering, for instance, the Fed can increase circulation and encourage lending by purchasing securities from banks. Alternately, if the Fed wants to remove dollars from the economy, it can sell securities from its account.

Read more: Who Is Satoshi Nakamoto?

For better or worse, bitcoin is a bit different. For one, the supply schedule is all but set in stone.

Unlike the monetary policy of state-issued currencies, which unfolds through political processes and human institutions, Bitcoin’s monetary policy is written into code shared across the network. Changing it would require an immense output of coordination and agreement across the community of Bitcoin users.

“Unlike most national currencies we’re familiar with like dollars or euros, bitcoin was designed with a fixed supply and predictable inflation schedule. There will only ever be 21 million bitcoins. This predetermined number makes them scarce, and it’s this scarcity alongside their utility that largely influences their market value,” crypto wallet company Blockchain.com wrote in a blog post ahead of the 2016 halving.

Another unique aspect of Bitcoin is Nakamoto programmed the block reward to decrease over time. That is another way in which it differs from the norm for modern financial systems, where central banks control the money supply. In stark contrast to Bitcoin’s halving block reward, the supply of the dollar has roughly tripled since 2000.

Nakamoto left clues that they created Bitcoin for political reasons. The first Bitcoin block features the headline of a newspaper article: “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

Many have come to interpret that statement as a sign of Nakamoto’s political beliefs and goals. If widely adopted, Bitcoin could potentially reduce the power banks and governments have over monetary policy, including bailouts of struggling institutions. As shown with the block reward, no central entity can create bitcoin outside of the strict schedule.

How does halving influence bitcoin’s price?

A bitcoin halving grabs so much attention mostly because many believe it will lead to a price increase. The truth is, no one knows what’s going to happen.

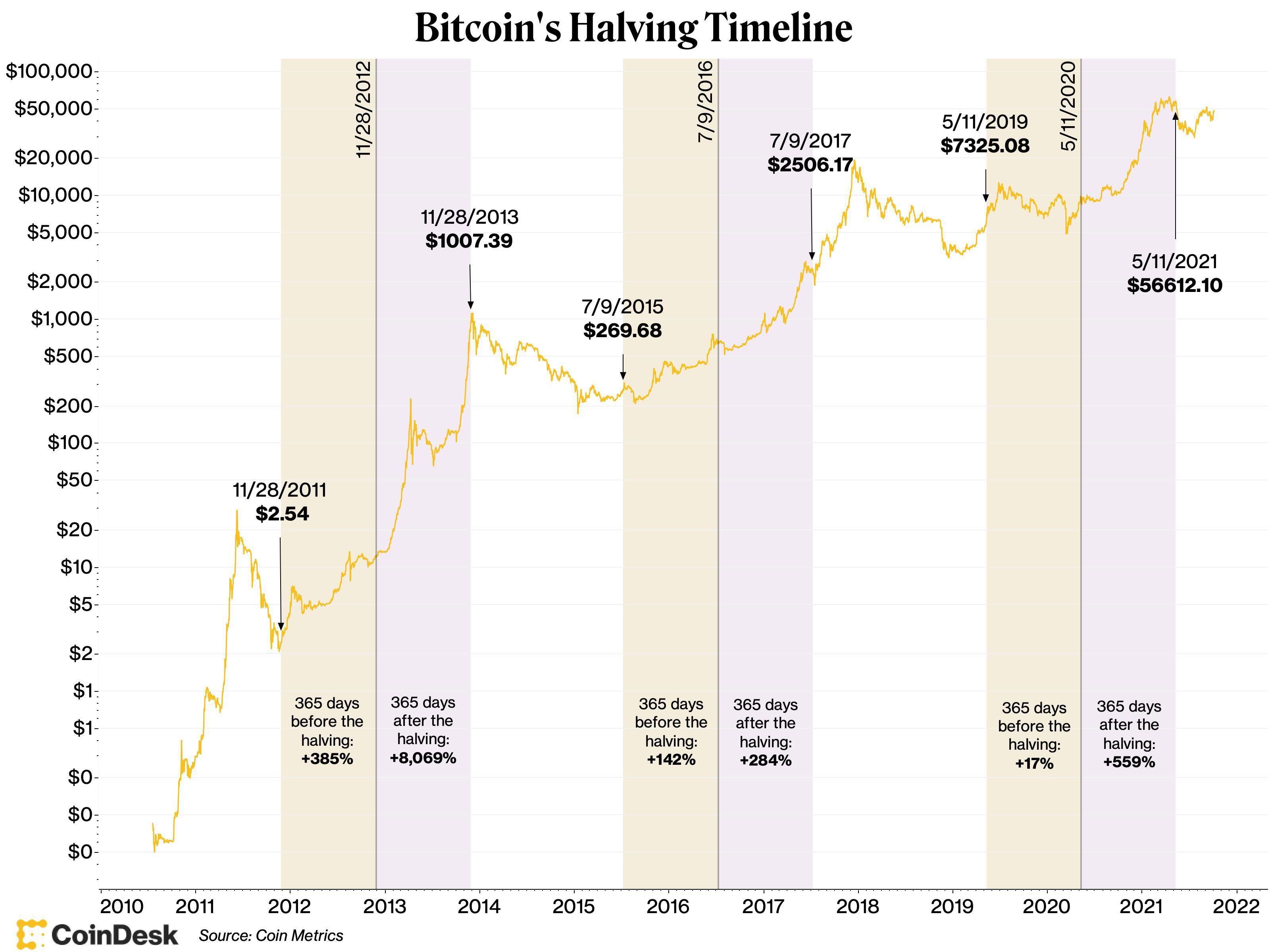

Bitcoin has seen three halvings so far, which we can look to as precedents.

The 2012 halving provided the first demonstration of how markets would respond to Nakamoto’s unorthodox supply schedule. Until then, the Bitcoin community didn’t know how a sudden decline in rewards would affect the network. As it turned out, the price began to rise shortly after the halving.

The second halving in 2016 was highly anticipated, with CoinDesk running a live blog of the event and Blockchain.com putting out a “countdown.” Each halving has encouraged vigorous speculation about how the event would affect bitcoin’s price.

On July 16, 2016, the day of the second halving, the price dropped by 10 percent to $610, but then shot back up to where it was before.

Read More: Bitcoin’s Third Halving Arrives

Although the immediate impact on the price of bitcoin was small, the market did eventually respond over the course of the year following the second halving. Some argue that the increase was a delayed result of the halving. The theory is that when the supply of bitcoin declines, the demand for bitcoin will stay the same, pushing the price up. Looking at bitcoin’s price 365 days after the second halving, we can see it rose by 284% to $2,506.

Looking at the most recent halving, we can also see bitcoin’s price continued to perform bullishly a full year after the event took place. This time, it rose by more than 559%.

Why do miners get these rewards?

Bitcoin wouldn’t work at all without block rewards.

As pseudonymous independent researcher Hasu put it, there are two parts to making Bitcoin work. “Bitcoin’s ledger state should answer the question of ‘who owns what, when?’” Hasu told CoinDesk.

The first part, “who owns what?” is solved by cryptography. Only the owner of a private key (which is like a secret access code) can spend the bitcoin.

The game theory that secures Bitcoin requires that a) miners have an incentive to mine honest blocks [and] b) miners have a cost … to attempting dishonesty.

“The second half (‘when?’) is the big challenge and was unsolved before Bitcoin,” Hasu explained. Otherwise, it’s easy for people to “double-spend” their coins, effectively creating money from thin air.

Without the block rewards, the network would be in chaos. Hasu explains that if they have enough computing power, miners can attack the network in two ways: By double-spending coins or by stopping transactions from going through. But they are strongly incentivized not to try either, because then they would risk losing their block rewards.

“The game theory that secures Bitcoin requires that a) miners have an incentive to mine honest blocks [and] b) miners have a cost … to attempting dishonesty,” Dubrovsky said.

In other words, miners will lose money if they don’t follow the rules.

The more computing power miners direct toward Bitcoin, the harder it is to attack the network because an attacker would need to have a significant portion of this processing power, known as the hashrate, to execute such an attack.

The more money they can earn by way of block rewards, the more mining power goes to Bitcoin, and thus the more protected the network is.

What happens when block rewards get very small or taper off entirely?

That is why the periodic decrease in rewards might eventually become an issue.

Miners need an incentive to do what they do. They need to get paid. They’re not running these expensive, electricity-guzzling computers for their health after all.

But the consequence of the decline in block rewards is that eventually, it will dwindle to nothing. Transaction fees, which users pay each time they send a transaction, are the other way miners earn money. (Theoretically, these fees are optional, although as a practical matter, a transaction without one might have to wait a long time to be processed if the network is congested; the size of the fee is set by the user or their wallet software.) The fees are expected to become a more important source of remuneration for miners as the block reward falls.

“In a few decades when the reward gets too small, the transaction fee will become the main compensation for nodes. I’m sure that in 20 years, there will either be very large transaction volume or no volume,” Nakamoto wrote.

But for a long time, Bitcoin researchers have been considering the possibility that transaction fees won’t suffice. For one thing, it means transactions might need to grow more expensive over time to keep the network secure.

It’s impossible to predict what will happen, but if we want a system that could last 100 years, we should be ready for the worst case.

“This cannot really work without very expensive transaction costs because Bitcoin cannot process huge quantities of transactions on-chain,” Dubrovsky said.

And, as discussed above, it is mining rewards that draw more computing power to Bitcoin, hardening it against attacks that try to circumvent the network’s rules. It’s unclear whether a future attenuated block reward will have the same allure for miners, even when supplemented with fees.

“I don’t think this halving will make Bitcoin significantly less secure, but in eight to 12 years, we could find ourselves in hot water,” Hasu said.

Part of the problem is that more than a decade after Bitcoin’s birth the market is still figuring out the true cost of protecting the network from attackers.

“Nobody knows the correct level of security needed to keep Bitcoin safe. Currently, Bitcoin pays out something like $5 billion per year and there are no successful attacks; however, there has been no price discovery. Bitcoin may be overpaying. To really find out the minimum level of security needed to avoid attacks, the mining rewards would need to be dropped to the point where attacks start happening and then increased until the attacks stop,” Dubrovsky argued.

“Of course, this would be catastrophic for Bitcoin as it’s designed now, but it could really come to some kind of scenario like this if rewards dwindle and the Bitcoin community doesn’t do anything about it,” he added.

Hasu said he “hopes” transaction fees will be enough to incentivize the security of Bitcoin in the end, but he thinks it’s worth anticipating the “worst case.”

“It should be clear that the incentive to attack Bitcoin today is larger than it was five years ago. We now have [former U.S. President Donald] Trump, [China President Xi Jinping] and other world leaders talking critically about it. The more Bitcoin grows, the more they might see it as a threat and might eventually feel forced to react. That would be the worst case, anyway,” Hasu said.

This question is an interesting one to ponder when thinking about Bitcoin’s future prospects, though it might sound like a far-off matter.

“It’s impossible to predict what will happen, but if we want a system that could last 100 years, we should be ready for the worst case,” Hasu said. “The worst case is demand for block space does not increase in the dramatic fashion that would be needed. As a result, block rewards would eventually trend toward zero.”

Bitcoin Halving Research ReportWant more depth and data on how to invest against the halving? CoinDesk Research has released Bitcoin: The Halving and Why It Matters, a research paper for investors. Download the report for free and sign up for the weekly investor newsletter, Institutional Crypto.

Updated 10/06/2021 to reflect the most recent bitcoin halving, which took place on May 11, 2020.