Windows 11 is officially here, but Microsoft added some strict new hardware requirements for its next-gen operating system. Microsoft is working with PC makers to develop Windows 11-ready PCs, and you may be able to upgrade to Windows 11 for free with your existing PC—provided that it meets the new criteria.

Windows 11’s hardware requirements, in fact, have quickly become the most controversial aspect of Microsoft’s new operating system. We’ve listed the CPU requirements below, as well as the available Windows 11 upgrade options if your PC’s components do not conform to them. Microsoft has also published a multipage document listing the detailed hardware requirements of Windows 11 (PDF), along with new webcam and touchpad requirements that have been added.

Fortunately, if your PC doesn’t meet the hardware requirements, you’ll have several years to replace it, as Windows 10 will be supported until 2025.

Check out our Windows 11 superguide for comprehensive news, reviews, tips and more about Microsoft’s new operating system.

Windows 10 vs. Windows 11 system requirements

For Windows 10, the PC hardware requirements necessary to run it are relatively tame: a 1GHz processor, 1GB of RAM (2GB for a 64-bit version of the OS), 16GB of storage, and a display capable of 800×600.

For Windows 11, you’ll need a more sophisticated PC. According to Microsoft’s list of PC hardware requirements for Windows 11, this is the first time that you’ll need a multicore processor to run Windows, though it won’t need to be that powerful: just a 1GHz, 64-bit processor with 2 or more cores. (Don’t worry about whether your PC includes a 64-bit chip, as virtually all PCs have included 64-bit processors since the 2000s.) There’s also a TPM requirement, which we’ll discuss below.

Windows 11 will require an 8th-gen Core CPU and above, according to the Windows 11 hardware requirements for Intel CPUs. A similar list of supported AMD processors on Windows 11 indicate that the Ryzen 2000 series and above is supported. Our performance testing of Windows 11’s Virtualization-Based Security feature shows a likely reason why those are the cutoffs. On the Arm side of things, Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 850 and up are also supported by Windows 11.

We’ve published a list of CPUs that support Windows 11, here. As of August 27, that list now includes the Intel Core X-series, the Xeon W-series, and the Intel Core 7820HQ, which features in the Microsoft Surface Studio 2. Microsoft has ruled out first-generation AMD Zen processors, however.

Eliminating older 7th-generation Core processors will certainly cut out a substantial portion of the PC market from a Windows 11 upgrade, though how many isn’t exactly clear. We’re already seeing Microsoft itself declare a substantial chunk of its Surface lineup ineligible for Windows 11 upgrades.

You will also need more memory. Microsoft is increasing the minimum amount of RAM to 4GB, and requiring a far larger amount of storage—64GB—then before. That’s because the amount of storage required is, according to Microsoft, “highly variable.” The storage controller must meet the Extensible Firmware Interface (EFI) 2.3.1 or higher.

Windows’ storage demand depends on what versions of Windows have been previously installed; the amount of storage already claimed by Windows; the size of your page file (also known as the swap file), which acts like a relief valve for your main system memory; and more. You’ll also need a DirectX 12-capable GPU, and at least a 720p display.

Finally, Microsoft publicized a couple of new requirements in its support document. New Windows 11 PCs (excluding desktops) shipped after January 2023 will be required to include a webcam, which Microsoft defines as “HD”—not 1080p, unfortunately, but just the same 720p webcams which ship with many PCs today. Microsoft also is insisting that all new Windows 11 PCs include a Precision touchpad.

Windows 11’s controversial TPM requirement

Microsoft is also adding new, stricter security requirements for Windows 11. You will now need a PC that includes a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0, a security coprocessor that’s not present on all PCs. (What’s a TPM?) A TPM includes a hardware-based random number generator, and can issue cryptographic keys to protect your data. TPMs also authenticate hardware devices. (Microsoft and AMD announced a complementary technology called Pluton in late 2020, originally developed for the Xbox, though Windows 11 PCs don’t appear to require it.) Your PC must also support UEFI and be Secure Boot-capable.

Microsoft originally instituted both a ”hard” and a “soft” floor of specifications to run Windows 11, designed around the TPM module specification. In June, Microsoft eliminated the “soft floor” and made TPM 2.0 a minimum requirement. If your PC doesn’t include this TPM capability (or if it includes just the older TPM 1.2 specification), it will not be eligible for Windows 11 and will be considered unsupported. Fortunately, there are tools that can tell you whether or not your Windows PC is eligible for Windows 11.

How to tell if your PC can run Windows 11

There are two ways to determine whether your PC can run Windows 11.

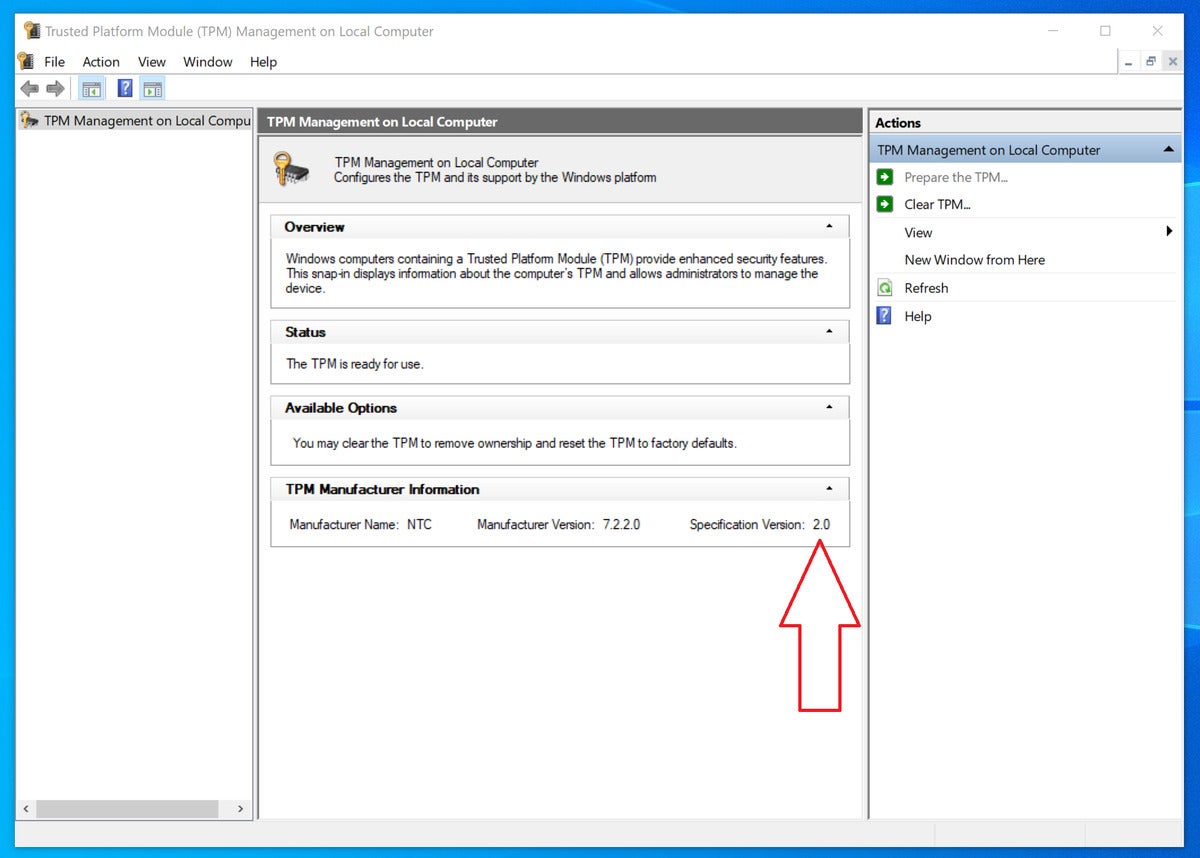

First, to figure out whether your PC contains a TPM, you can just ask it. If you type tpm.msc into your Windows 10 PC’s search bar, your PC will open the Trusted Platform Module Management app. You’ll then be to scroll down to the TPM Manufacturer information and see whether a TPM is installed, and whether it’s TPM-certified.

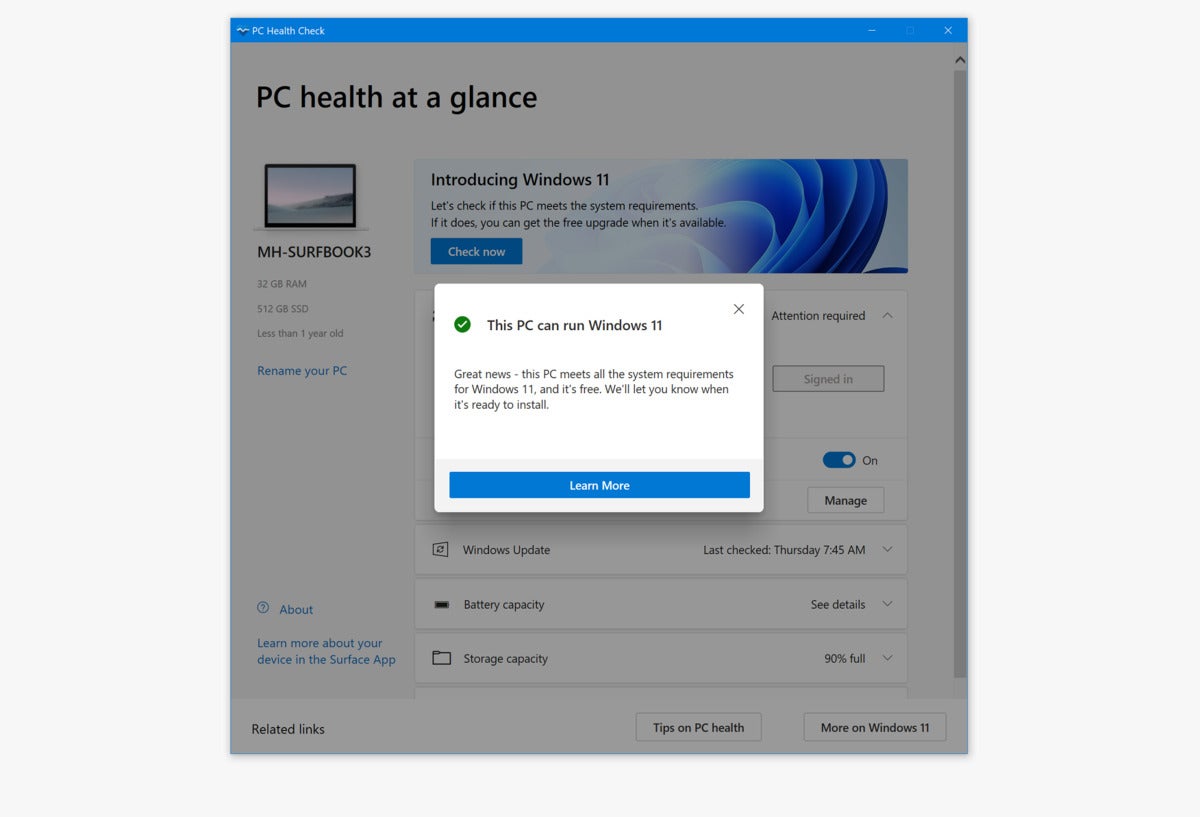

Second, Microsoft is providing a free app to determine whether your PC is capable of running Windows 11: the PC Health Check app. (Warning: That link begins a download of the tool.)

PC Health Check is already live on Microsoft’s site, and it’s worth downloading. It’s a small Win32 app that provides a summary of what’s on your PC. It also offers a one-click check of your PC’s capabilities at the top of the window, to see whether you can run Windows 11. Microsoft said on June 26 that it updated the PC Health Check app to provide more information about what would make a PC ineligible for Windows 11.

There’s also a third-party, unsupported tool called WhyNotWin11, which is available on GitHub. WhyNotWin11 is not supported by Microsoft, and Windows SmartScreen will likely flag it if you run it. (Use at your own risk.) WhyNotWin11 was designed to provide even more granular information about your PC, and why it might not be eligible for Windows 11.

How to run Windows 11 on an older PC

Originally, Microsoft drew a line in the sand and insisted that all PCs meet these hardware requirements. But the company is now quietly saying that older PCs will be able to run Windows 11, too, but only for a very short time.

“Unsupported” PCs must still meet some minimum specifications, which appear to include a supported 64-bit CPU, 4GB of memory, 64GB of storage, UEFI secure boot, graphics requirements and TPM 1.2, to run Windows 11.

Microsoft originally said that a PC that met these minimum requirements would be able to download a Windows 11 ISO file and run it, allowing unsupported PCs to run Windows 11 until the official release. But then Microsoft changed its tune: Yes, older PCs will be able to download Windows 11 ISOs, but won’t be able to receive Windows updates—an enormous security risk. Then, Microsoft also blocked unsupported PCs from even participating in Windows 11 Insider testing. Here’s the bottom line: you can still download Windows 11 via an ISO on an unsupported PC that doesn’t meet Microsoft’s hardware requirements, but your security risks will grow as Microsoft releases patches for the OS that your PC will not receive.

The other option: Windows 10

If you can’t run Windows 11, you have a few options. You can stick with Windows 10, which Microsoft will support until it’s “retired” in 2025. Or you can buy a “Ready for Windows 11” PC, which PC vendors will begin releasing later this year. If all this discussion over the Windows 11 hardware requirements seems like too much bother, buying a new Windows 11 PC may be the way to go.

This story was updated on October 5 to mention Windows 11’s general availability.

As PCWorld’s senior editor, Mark focuses on Microsoft news and chip technology, among other beats. He has formerly written for PCMag, BYTE, Slashdot, eWEEK, and ReadWrite.